In a Hawks Insiders exclusive, Tony Wilson - author, broadcaster and son of 1971 Premiership star Ray - pays tribute to Don Scott following his official induction as the ninth Legend of the Hawthorn Footy Club.

Many Hawks, including my father who was standing in the centre at the time, regard it as the winning moment of the 1971 Grand Final.

The ball is about to be bounced for the last quarter. It’s a wet, miserable afternoon. Hawthorn has kicked five goals for the game and trails St Kilda by 20 points. Hudson is concussed. At half time, John Kennedy resolved to substitute the game’s greatest goal kicker (there was no interchange) until the doctor realised Robert Day thought it was Sunday.

The Saints had dominated the third quarter. For his three quarter time address, Kennedy allowed an uncharacteristic note of negativity to creep in, “Is this going to be the one game that you lose? Well if you are going to lose, make sure you go down gloriously!” The coach departs.

The shellshocked team is ready to disperse when a booming voice calls the team together. It isn’t the captain, David Parkin. It’s the 23-year-old in the #23, Don Scott. “We’re not going to lose this game! And it will start with me!” he roars. He roars hope, and possibility, and inspiration.

Dad remembers none of it.

But he remembers the next bit. Don Scott pawing at the ground, eyeing off Brian Mynott. And then Don charging in, leaping high and fisting the ball 10 metres forwards, into the arms of Meagher. Famously, it would be a seven goal quarter with 4.2 to the previously kickless Keddie, and one bouncing miracle to Scott himself.

The young ruckman had 21 kicks and 20 hitouts for the day, against the tag team of Mynott and Ditterch. If the AFL awards retrospective Norm Smith Medals, and they should, Don will add that accolade to his three premiership medallions.

In that moment, he showed he was a leader for a crisis. He’d assume the captaincy in 1976, and if the Hawthorn way was carved into stone by Kennedy, Scott was first among his disciples.

He was a legendary trainer, a natural athlete in the Jim Stynes mould, who was first ruck in Hawthorn’s Team of the Century, despite standing just 190cm. He won hit outs against taller, higher jumpers like Carl Ditterich and Peter Moore by simply wanting it more. He used his prodigious aerobic ability to run and run, almost like a modern midfielder, hurting his opponents in the best and fairest way. And then, as his tribunal record demonstrates, he’d hurt them in other ways too.

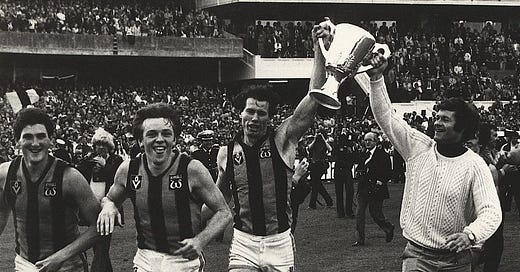

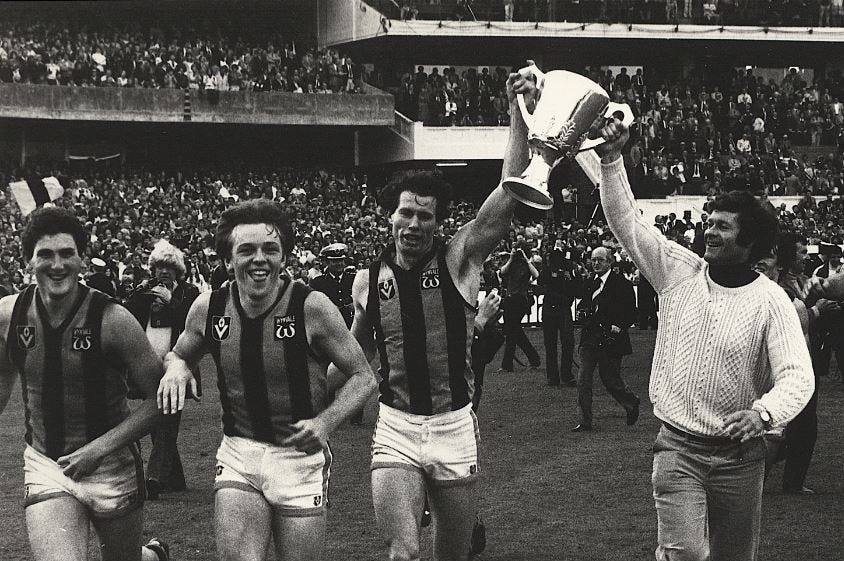

He lifted the cup twice as captain. We were the mighty fighting Hawks. There were none mightier, or fightier, than Don Scott.

Don wasn’t just a warrior on the field. He was willing to start the fight for better pay and playing conditions as president of the Players Association. This was at a time when the average player earned less than $100 a game to play in front of full houses. Every modern player owes a debt to Don Scott and his fellow AFLPA pioneers.

When his friend David Parkin was sacked as coach at the end of 1980, the fiercely loyal Scott sniffed an injustice. It was just two years since the 1978 premiership. He thought the board was acting hastily. Scott attempted to rally a players strike in support of Parkin, as well as for better pay.

On the first night of training of the Jeans era, the players intended not to take to the track. Then, chairman of selectors John Kennedy went up to the Players Room and spoke, loudly and memorably. “We trained,” laughs Ian Paton. “Kanga dissolved our strike action in about two sentences.”

In 1981, Scott played his 300th game, while maintaining a vow of silence within the club walls to protest grievances relating to the Parkin sacking. He retired at the end of 1981, feuding with the club, and invited only a dozen or so close friends to the Waiters Club for his 300th game celebrations. My dad was one of them.

He went around the table and told each person why they were invited. “Ray, you’re here because you ran through big Carl in the ‘71 Grand Final.” When he got to his changing ruckman Bernie Jones he said, “Bernie, you’re here because I said I wouldn’t speak to anyone this year, and I haven’t, and every night you’ve come up to me and said, ‘How are you going Don, how was your day, Don?’ … I didn’t answer you and yet you kept talking to me, and that’s why you’re here.”

“A great leader in wartime,” Dad grins. “Maybe not so great in peacetime … Don doesn’t mind fighting.”

In 1996, when Hawthorn’s future was on the line, Don fought. At a time when every expert financially-trained eye said merger was inevitable, 1971 premiership wingman Leon Rice told Don to fight it, because he knew the powers of the combatant. Days later, with Rice and four other supporters, Don held a press conference in the Hawthorn Museum.

When a reporter asked about previous run-ins with the club. Don thumped the table so hard the glasses went flying. “I don’t care about the past!” he roared. “All I care about is the future of the Hawthorn Football Club, and when you’ve got mongrel, mixed with passion, you’ve got a bloody good brew.”

Quickly Scott built his army. Within weeks, the children of the '70s and '80s who’d experienced so much joy, reached into their pockets for Operation Payback as Don had said they would. Then he stood on a stage at the Camberwell Town Hall and ripped a Velcro Hawk from a Melbourne guernsey. And of the brown and gold — “They might not be the prettiest colours, but they’re ours!” It’s all the stuff of legend. Of course he becomes an official legend. He saved the club.

In true Scott style, he didn’t slip quietly into the deified realm he might then have inhabited. His son Doug was recruited with the club’s seventh pick in the 2003 pre-season draft, but then in 2004 was allowed to train and play for five months on a misdiagnosed broken leg. Don was furious, and Doug was awarded compensation. Don and the club fell out again.

He left the board after withdrawing a challenge to Ian Dicker in 2004. Since then, Scott has not been closely involved at Hawthorn. He’s lived on the Mornington Peninsula, pursued his love for equestrian and eventing, and run a property maintenance business which in recent years has employed fellow VFL legends Bernie Quinlan and Tony Jewell.

One of the properties they’ve maintained is Mum and Dad’s at Red Hill, and some of my true ‘footy’ highlights this decade have been Don Scott screaming at Superboot about the quality of his whipper-snippering.

He's still close to many of the players of the Kennedy and Parkin eras, including Dad, and for those within the circle, there’s an almost military-level loyalty. When Dad was going through some tough months at the end of the '90s, Don called him every night, at the same time, to ask how he was. He’s a good friend, and especially good on the phone. He occasionally rings me to ask about the Socceroos and the Matildas. I offer low level expertise.

One of the reasons I became involved in the Hawks For Change group was the manner in which Jeff Kennett treated Don with regards to his Legend award. Kennett wanted it to be presented at the AGM, a soulless and administrative occasion. Don wanted a celebratory function which could include former teammates.

The eight previous Legends — John Kennedy Snr, Graham Arthur, Leigh Matthews, Michael Tuck, Jason Dunstall, David Parkin, Peter Knights and Peter Hudson — all had their special nights. Kennett decided not to budge. Don decided not to accept the award. Kennett thought he could out-Don Don.

Last night, at the AGM, Don was announced as the ninth legend of the club, but he didn’t appear on Kennett’s Zoom, and the award will be presented at a celebratory function. You don’t out-Don, Don.

Congratulations to a club saviour and a legend. May the long overdue function in 2022 be everything he deserves. And on that night, may he treat us to something typically ‘Don’.

I’m thinking something daring involving a silk scarf, leather bag, waistcoat and suede.

You can buy a signed copy of Tony Wilson’s book on the 1989 Grand Final here.